About Food Systems

A Food Systems Framework

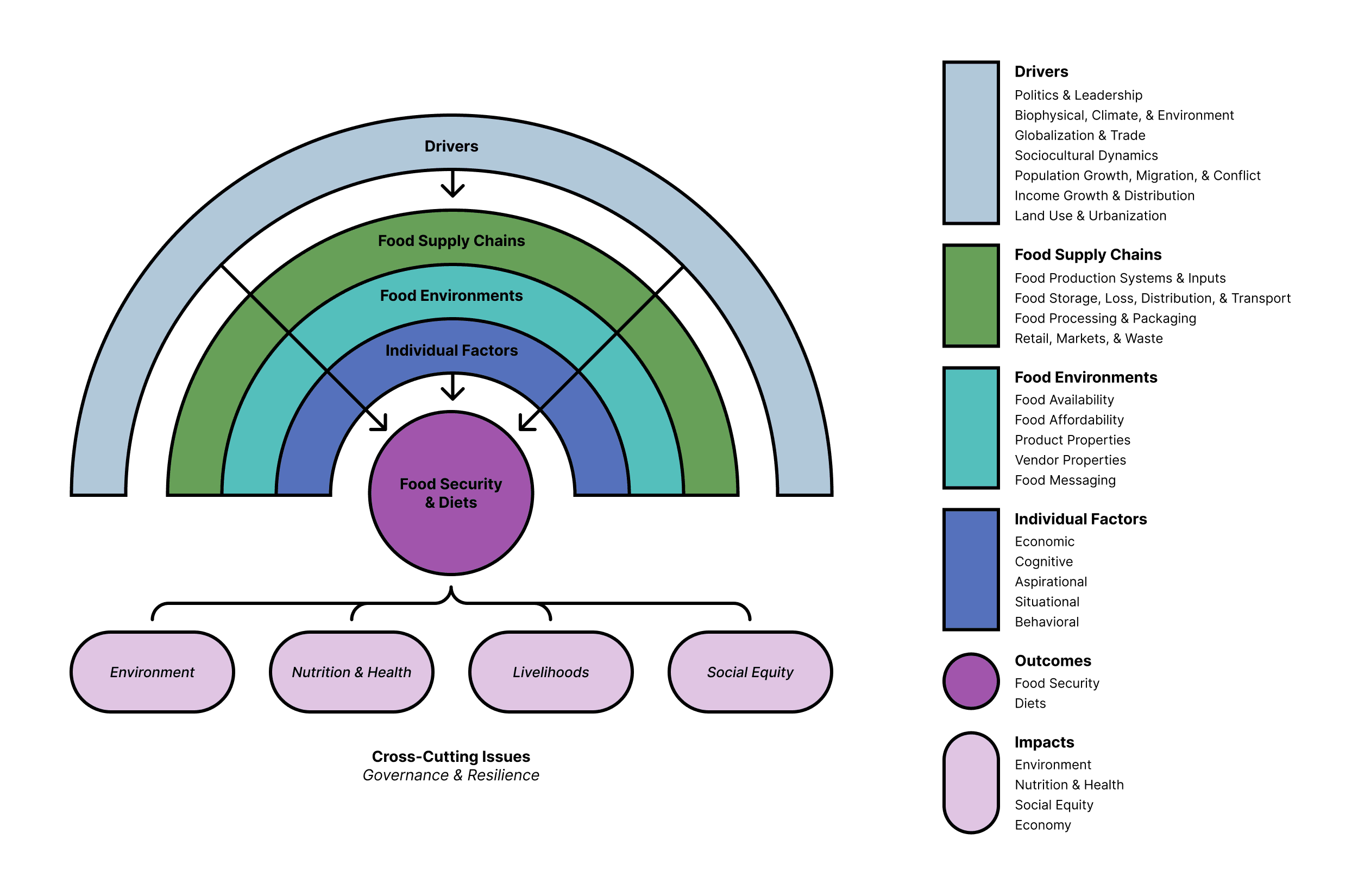

Food systems comprise all the people, institutions, places, and activities that play a part in growing, processing, transporting, selling, marketing, and, ultimately, eating food. Food systems influence diets by determining what kinds of foods are produced, which foods are accessible, both physically and economically, and peoples’ food preferences. They are also critical for ensuring food and nutrition security, people’s livelihoods, and environmental sustainability

As shown in the framework above, the different parts of the food system include food supply chains, food environments, and individual factors. Food systems also encompass crosscutting issues and drivers (factors that push or pull at the system, some being exogenous to food systems). The components, crosscutting issues, and drivers all shape food systems and can lead to both positive and negative outcomes.

Components of Food Systems

Food Supply Chains

The food supply chain includes all the steps needed to produce and move foods from field to fork. These steps consist of agricultural production, storage and distribution, processing and packaging, and retail and marketing, among others and involve farmers, processors, wholesalers, transporters, and retailers.

The steps in the food supply chain are all connected. Changes in one step can affect other steps along the chain as well as other components of food systems such as the nutritional quality and affordability of foods.

Food supply chains operate at different scales and levels, depending on the food system. In rural and geographically isolated communities, food supply chains may be short — farmers and food producers may produce food for their own consumption or sell it to their neighbors in the local market. In large urban settings, food supply chains may be much longer and more complex — food is typically produced farther away and more people are involved in its production, processing, packaging, and retail. Food supply chains are undergoing rapid transformations, especially in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), often leading to more interaction between these urban and rural settings and actors.

Food Environments

The food environment is where people interact with the food system for the purpose of acquiring and eating food. This includes physical places where people buy food, such as stores or markets, and the food messaging people are exposed to. It also includes social, economic, and cultural factors. Food availability, affordability, safety, quality, convenience, and advertising are all part of the choice architecture of the food environment. These characteristics of the food environment affect diets by influencing the way people access foods.

Individual Factors

Individual factors include a person’s economic status, overall life situation, thought process, and behavior. These factors all affect how people interact with their food environment and, ultimately, what foods they buy, prepare, and eat. For example, a person’s income might determine what foods are affordable and their nutrition knowledge or awareness of environmental impacts may affect what they purchase and eat. Work and home environments can affect how much time people have to shop for and prepare food. There is a large body of nuanced research on individual factors, but publicly available data sourced across countries are lacking.

Cross-Cutting Issues

Governance

Governance encompasses the commitment, capacity, and accountability to identify, implement, promote, and monitor solutions with the potential to positively impact food systems outcomes. This includes the public sector, private sector, civil society, and individual people and spans multiple geographic scales and administrative levels, requiring different priorities to be addressed and different coordination mechanisms to be present at various levels. Successful governance requires creating a shared vision through inclusive, participatory processes to identify priorities and provide guidance on positive outcomes. Power imbalances, such as corporate concentration of power, hinder achieving this shared vision.

Resilience and sustainability

Food systems resilience is the ability of different individual and institutional food system actors to maintain or quickly recover the key functions of that system despite the impacts of disturbances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, or the numerous recent extreme weather events. Resilience can be measured at different levels from a country to an individual. A lack of resilience can lead to food shortages or price volatility and impact food security. The multitude and complexity of the interrelated shocks and stresses makes it imperative to improve food systems resilience.

Food systems resilience is a necessary condition for sustainability, which encompasses all food systems components and outcomes. Food systems sustainability recognizes human rights, food and nutrition security, just livelihoods, and environmental health now and for future generations all as imperative goals. However, it may not be possible to improve all food systems outcomes simultaneously, thus understanding and managing the synergies and trade-offs between different food systems outcomes is critical.

Drivers of Food Systems

Environment and Climate Change

The effects of unmitigated climate change are already causing increased food insecurity. At the production level of the food system, climate change can lead to declines in fish populations and crop yields. Staple crops grown in high carbon dioxide conditions will likely have reduced nutrient content (e.g. protein, iron, and zinc) which affects the quality of people’s diets. At the storage and distribution stage of the food system, higher temperatures from climate change can also lead to more losses. Extreme weather events also cause losses at production, storage, and distribution levels. Food prices may increase because of declining crop yields and agricultural losses.

Globalization and Trade

Globalization makes people and countries more interconnected and interdependent. It shapes local economies and affects human health and nutrition in both positive and negative ways. Trade may create new employment opportunities, but it can also increase competition for local producers, which may reduce prices for domestic products and threaten the livelihoods of smallholders. Trade can allow people to access foods that may not be easily grown where they live or are less available during a particular season. This increases the diversity of the food supply and access to seasonal foods year-round. It may make certain foods less expensive through efficiency and competition. The lowered cost of imported food and animal feed can increase access to animal source foods and lead to higher protein intake, which is important for areas with high rates of undernutrition. However, globalization and trade can also have adverse effects on diets and nutrition. Unhealthy foods have become increasingly accessible and inexpensive around the world, partly due to trade policies and widespread advertising. People’s diets have changed from more traditional ones high in minimally processed foods to those high in animal source foods and ultra-processed foods high in salt, unhealthy fats, and added sugars. All of these changes have contributed to the increasing burdens of non-communicable diseases.

Income growth and distribution

As a country’s average income grows, nutritious foods – such as animal source foods and fruits – become more accessible. Increased demand for animal source foods can stress food systems by putting more demands on land and water resources and increasing greenhouse gas emissions. Rising incomes can also lead people to buy more unhealthy foods, such as ultra-processed foods. In high-income countries (HICs), healthier foods – like fresh fruits and vegetables – are typically more expensive than highly-processed, packaged foods. These less expensive foods tend to be higher in salt, unhealthy fats, and added sugars. Increased income inequality makes healthy foods inaccessible for many.

Urbanization

Urbanization is occurring globally, with the biggest increases in urban populations taking place in Africa and Asia. Urbanization shapes a country’s food system – it creates longer food supply chains and limits agricultural land. Urbanization changes the food environment by increasing the number of supermarkets in an area. Additional supermarkets can increase access to both healthy and unhealthy foods, including more ultra-processed foods. Urbanization is also linked to increased incomes, demand for convenience foods, and eating outside of the home. For people with low incomes, urbanization can lead to food deserts and swamps. In these areas, access to healthy, fresh food is limited, but unhealthy fast foods and ultra-processed foods are unfortunately, plentiful.

Increased attention is being placed on the way that linkages between cities and rural areas can be leveraged to revitalize rural economies and increase access to healthy diets for both urban and rural populations.

Population Growth and Migration

From 2017 to 2050, the world’s population is expected to increase by more than two billion people. Countries in Africa and Asia will experience the most rapid population growth. Increases in population put more stress on the current food system. Due to global trade and migration, population growth in one country can affect the food system in other regions as well. Additionally, countries may not be prepared for the influx of people fleeing conflict or severe weather events. Under these pressures, food systems may not be able to supply everyone with a healthy diet.

Politics and Leadership

A region’s policies on agriculture, nutrition, and trade affect food systems. Economic policies on agricultural subsidies and trade can influence the availability and affordability of certain foods, which in turn can affect dietary intake. Governments can implement dietary guidelines to promote healthy diets or tax policies to discourage eating unhealthy foods like sugar-sweetened beverages and ultra-processed foods. Political will and investment are needed to make sure there are sufficient resources to create a sustainable food system.

Socio-Cultural Context

Social and cultural traditions shape diets by influencing what foods are desirable, when and how meals are prepared, and what traditions are practiced. In some cultures, food may reflect a person’s social status in society or the household. Foods associated with a higher wealth status may be more desirable. In most cultures, food is a central part of holidays and traditions. Strong cultural ties to traditional foods and meal practices could work to prevent the shift to diets high in ultra-processed foods and reliance on fast food. In many cultures, certain foods are avoided for reasons such as life stage (adult vs. childhood foods) or gender. In particular, culture and social norms has a strong influence on what people eat while pregnant or lactating.

Outcomes of Food Systems

Diets and Food Security

Food security exists when “all people at all times have physical, economic, and social access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” and is a prerequisite for healthy diets. Diets are influenced by all aspects of the food system, and they impact nutrition and health. A healthy diet starts early in life and includes a diversity of foods — starchy staples, legumes, fruits, vegetables, and animal source foods, like meat, eggs, and dairy. It balances the intake and expenditure of energy, and limits salt, unhealthy fats, added sugar, ultra-processed foods, and sugar sweetened beverages.

Throughout the world, people still do not have access to adequate calories or a diversity of healthy, nutrient-rich foods. This lack of access results in hunger and micronutrient deficiencies. Rising incomes have increased the availability and accessibility of nutrient-rich foods like fruits, vegetables, and seafood. However, globalization and rising incomes have also contributed to people eating more unhealthy foods, like ultra-processed foods and sugar sweetened beverages.

Diets also have large impacts on the environment. Diets and food systems have major impacts on the use and degradation of land and water resources, as well as on greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

Nutrition and Health

Healthy diets are essential for nutrition and health. Poor diets are one of the main risk factors for disease and deaths globally. Unhealthy diets can lead to undernutrition, which is associated with poor cognitive development and increased susceptibility to infections. Diets that lack essential nutrients may lead to micronutrient deficiencies. Children, women, and other nutritionally vulnerable populations are especially susceptible to poor health outcomes from these deficiencies.

Diets that exceed recommended energy intake and are high in salt, unhealthy fats, and added sugar can lead to overweight, obesity, and diet-related non-communicable diseases, like diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Diets high in sodium and low in whole grains, fruit, vegetables, nuts, and omega3-fatty acids contribute to an increased risk of death.

Food safety, antimicrobial resistance, and pesticide usage also affect people’s health, especially those who work within the food system

Livelihoods, Poverty, and Equity

Globally, the food system is one of the main sectors of employment and supports the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people. However, incomes earned in food systems often fall short of a living wage and many of the people working in food systems are among the poorest and most marginalized in the world. While many of the world’s poorest work in agriculture, poverty affects workers throughout food systems, across the entire value chain, in both rural and urban areas. Livelihoods tied to food systems are also mired in violations of worker’s rights including slavery, child labor, harassment, and unsafe working conditions. Women and migrants are especially vulnerable to exploitation. Realizing just and equitable livelihoods for all who work in food systems requires institutional changes, policy support, and investments.

Environment

Food systems have large impacts on the environment, both locally and globally. They impact climate, land and water use, biosphere integrity, and pollution. Humans have exceeded safe limits on climate, water pollution, and biodiversity globally and on freshwater use locally. These areas are all interconnected, and interactions are often amplifying.

In agriculture, land is often cleared and then fertilizers are applied and freshwater is used, which can lead to eutrophication in both freshwater and ocean systems, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions. Global food systems account for 21-37% of total greenhouse gas emissions, food production uses approximately 40% of ice-free land, and is responsible for 70-80% of freshwater use.

The environmental impacts vary widely based on what foods are being produced and the methods of production. Producing ruminant meat (e.g., beef, lamb) and dairy can be especially environmentally damaging in many contexts. Production can require large areas of land and water and produce large amounts of greenhouse gas emissions. Intensive agriculture requires more fertilizer and pesticide use. In addition, the practice of mono-cropping – growing the same crop over an extended area – and cash crop production can lead to biodiversity loss. This can result in soil degradation and a food system that is less resilient to droughts or other extreme weather events.

Food System Types

The FSD team developed this food systems typology to highlight common patterns in food supply chains and food environments that exist across countries. Countries have been categorized into five types of food systems. By comparing these different food system types, stakeholders can understand the complexity of food systems and begin to identify priority areas of action within their own food systems. It should be noted; however, that countries within one food system may still be very different from each other. There are also many types of food systems that can exist within a single country, as different regions of a country and different foods include a mix of traditional and modern characteristics.

Rural and Traditional

In rural and traditional food systems, farming is mainly done by smallholders, and agricultural yields are typically low. Among most farmers, production is typically focused on staple crops, some of which they keep to eat, and a limited number of cash crops. Food imports represent a small percentage of domestic consumption. Supply chains are short due to smaller urban populations, resulting in many local, fragmented markets. The lack of refrigeration and storage facilities results in large food losses for some crops, which may make producers less likely to diversify into perishable foods. It can also contribute to the fragmentation of markets. The quantity and diversity of foods available varies seasonally, often with a pronounced lean season. Seasonal price swings tend to be large. Many countries with rural and traditional food systems are experiencing rapid growth in rural non-farm employment opportunities (e.g., sales of agricultural inputs, basic food processing, small-scale trading, and storage). Food is mainly sold in informal market outlets, including independently owned small shops, street vendors, and central/district markets. Supermarkets are rare outside of capital cities, though they are beginning to grow in number along with fast food chains. Compared to other types, a greater proportion of countries in this food system type have adopted mandatory or voluntary fortification guidelines for staple foods to combat micronutrient deficiencies.

Informal and Expanding

In informal and expanding food systems, agricultural productivity is higher on average than in rural and traditional food systems. The use of inputs (e.g., seeds and fertilizer) is greater. Medium- and some large-scale farms are beginning to emerge. Modern food supply chains are common for grains and other dry foods. While there are still small-scale processors, many large-scale processors and centralized distribution centers have also emerged. Modern chains are also emerging for fresh foods, though traditional supply chains continue to dominate for these foods due to weak cold chains and inadequate market infrastructure. Processed and packaged foods are available in both urban and rural areas. Food processing may include a combination of locally sourced and imported ingredients. Demand for convenience foods increases as the formal labor force grows and includes more women. Urbanization and income growth also play a role. Supermarkets and fast food are rapidly expanding and, compared to rural and traditional food systems, are more accessible. However, most people continue to obtain most of their food from informal market outlets, especially for fruits, vegetables, and animal source foods. Few food quality standards are in place and advertising is not regulated. As in rural and traditional food systems; however, many countries have fortification guidelines for staple foods.

Emerging and Diversifying

In emerging and diversifying food systems, an increased number of medium- and large-scale commercial farms co-exist alongside large numbers of small-scale farms. These small-scale farms are more linked to markets than in more traditional food system types. Modern supply chains for fresh foods, including fruits, vegetables, and animal source foods, are developing more rapidly. Urban areas source both dry and fresh foods through longer supply chains and rely on food imports more than traditional and informal food systems. Processed and packaged foods are more available in rural areas and there is less seasonal fluctuation in the availability and pricing of perishable foods. Supermarkets are common even in smaller cities and towns, and their market share is growing rapidly. Processed foods, including ultra-processed foods, are common in urban areas and also found in many rural areas. Most fresh food continues to be acquired through informal markets, but the share of supermarkets is rising and significant. Food safety and quality standards exist but are enforced mainly within formal markets due to limited government monitoring capacity. A greater proportion of countries in this food system type have adopted food-based dietary guidelines.

Modernizing and Formalizing

In modernizing and formalizing food systems, agricultural productivity is generally higher than in emerging, informal, and traditional systems. Larger farms rely more on mechanization and input-intensive practices. Food supply chain infrastructure is more developed, which results in fewer food losses on the farm and beyond the farm gate. On the other hand, food waste is rising rapidly, and spoilage at the end of the supply chain remains a challenge. Food and beverage manufacturing represent a smaller percentage of overall manufacturing because countries in this type have more manufacturing in non-food sectors. Dietary energy is derived from diverse food sources and better national distribution chains enhance the role of food imports in enabling more year-round availability of diverse foods. Multiple supermarket chains exist within cities and larger-sized towns, but their growth is slower than in late transitional systems. These supermarkets and other modern retail outlets hold a large share of processed and dry goods sales, have captured a larger market share of fresh foods, and low-income consumers are much more likely to shop in them. Government regulation and monitoring of food safety and quality standards are more common. Most recently, aggressive food labeling is emerging for ultra-processed foods.

Industrialized and Consolidated

In industrialized and consolidated food systems, farming is a small proportion of the economy. There are a small number of large-scale, input-intensive farms that serve specialized domestic and international markets (e.g., horticulture, animal feed, processed food ingredients, biofuels). Market consolidation is common — large-sized food retailers procure directly from processors and urban wholesalers procure directly from farmers, which reduces the number of intermediaries along the supply chain. Supply chains are long, with national and international sourcing of nearly all types of foods. Supermarket density is high in urban and metropolitan areas. In general, only small towns lack a supermarket and most medium-sized towns have multiple outlets. The formal food sector has captured nearly all of the food eaten domestically, including fresh foods. There is growth in luxury food retail, as well as “fast-casual” restaurants, which market higher-quality fast food. Pockets of food insecurity persist, along with economic disparities. A greater proportion of countries with this type of food system have adopted policies that ban the use of industrial trans fats and encourage the reformulation of processed foods to reduce salt intake.

Question or comments? Email us at info@foodsystemsdashboard.org